|

The moment I finally accepted that irrelevant experiences do not and cannot exist - that everything experienced contains various shades of relevance - I took my first step toward understanding this world and my place in it.

4 Comments

American literature abounds with memorable symbols - the white whale, the scarlet letter, and the red badge of courage to name but a few. But of all the symbols American writers have employed in their works, the one that has impressed me above all others - yes, even more than Melville's white whale with all of its metaphysical connotations intact - is the oculist's billboard F. Scott Fitzgerald plants in the middle of the valley of ashes in his novel, The Great Gatsby.

Of course, nearly everyone who has read The Great Gatsby would argue the green light at the end of Daisy's dock is the most memorable symbol Fitzgerald weaves into his tragic narrative of ambition and yearning. I do not object to this because as the central symbol of the narrative, the green light is indeed the most memorable and is excellent within its own right. But the eyes of T.J. Eckleburg contains a haunting element the green light lacks - the brooding gaze of God, unceremoniously abandoned and virtually forgotten, staring out over a landscape marred by the spent debris of the greed, lust, and hedonism that have taken His place. The eyes of T.J. Eckleburg make their first appearance in Chapter 2 when Nick accompanies Tom to the valley of ashes: About half way between West Egg and New York the motor-road hastily joins the railroad and runs beside it for a quarter of a mile, so as to shrink away from a certain desolate area of land. This is a valley of ashes—a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air. Occasionally a line of grey cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-grey men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud which screens their obscure operations from your sight. But above the grey land and the spasms of bleak dust which drift endlessly over it, you perceive, after a moment, the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg. The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a nonexistent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness or forgot them and moved away. But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days under sun and rain, brood on over the dumping ground. Those familiar with T.S. Eliot's The Wasteland quickly catch the symbol and its deeper meaning, but those unfamiliar with Eliot's poem probably only regard the eyes as a component of Fitzgerald's masterful description of the barren landscape separating the skyscrapers of Manhattan from the lush gardens of Long Island. When I first encountered the eyes of T.J. Eckleburg, I was struck by the subtle obviousness of the symbol and the ethereal concreteness with which Fitzgerald employs it. Like all memorable symbols, Eckleburg's eyes to not impose themselves upon the reader in an overbearing manner. There is nothing domineering or tyrannical in its appearance. Nevertheless, it enters the text like a screaming whisper - muffled words transmitted in a language that is at once both foreign and familiar. Fitzgerald allows the ghostly quality of Eckleburg's eyes to linger and haunt the reader until the very end of the novel when the deeper implications of what the eyes represent is laid out plainly for those who lacked the eyes to see and the ears to hear what the oculist's billboard heralded near the beginning of the novel. Wilson’s glazed eyes turned out to the ashheaps, where small grey clouds took on fantastic shape and scurried here and there in the faint dawn wind. ‘I spoke to her,’ he muttered, after a long silence. ‘I told her she might fool me but she couldn’t fool God. I took her to the window—’ With an effort he got up and walked to the rear window and leaned with his face pressed against it, ‘—and I said ‘God knows what you’ve been doing, everything you’ve been doing. You may fool me but you can’t fool God!’ Standing behind him Michaelis saw with a shock that he was looking at the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg which had just emerged pale and enormous from the dissolving night. ‘God sees everything,’ repeated Wilson. ‘That’s an advertisement,’ Michaelis assured him. Something made him turn away from the window and look back into the room. But Wilson stood there a long time, his face close to the window pane, nodding into the twilight. The gently obscured symbol Fitzgerald gingerly erects in Chapter 2 shatters like a delicate porcelain vase dropped on the narrative's floor in Chapter 8. Many readers are repulsed by the heavy-handed nature of Fitzgerald's unveiling and liken Wilson's moralistic utterances to being struck by a falling piano, but I have always admired the simple sincerity Fitzgerald employs at this deep point in the novel. Like a magician revealing the secrets behind his tricks, Fitzgerald removes all possibilities for alternate interpretations of Eckleburg's eyes. A narrow variety of interpretations of the green light is permitted here, and there is space enough for these interpretations to curl up like cigarette smoke and linger for decades in the diaphanous air hovering over coffeehouse tables, but when its comes to the oculist billboard, Fitzgerald is both a spoiler and a tyrant. The eyes of T.J. Eckleburg can mean one thing and one thing only. Needless to say, most readers find this non-negotiable quality of Eckleburg's eyes overly-simplistic and unsightly, but in my mind, it is precisely the quality that makes the symbol so memorable. Anyone who still believes the European Union is anything other than a building block toward a totalitarian one-world government is either willfully blind or inexplicably dense. Many errantly believe the EU was created to build a union of independent nations, and they continue to harbor this belief even when leaders from the European Commission and the European Parliament openly declare the opposite. Case in point, outgoing EC President Jean-Claude Juncker, who recently uttered the following remark about Viktor Orbán, the Prime Minister of Hungary.

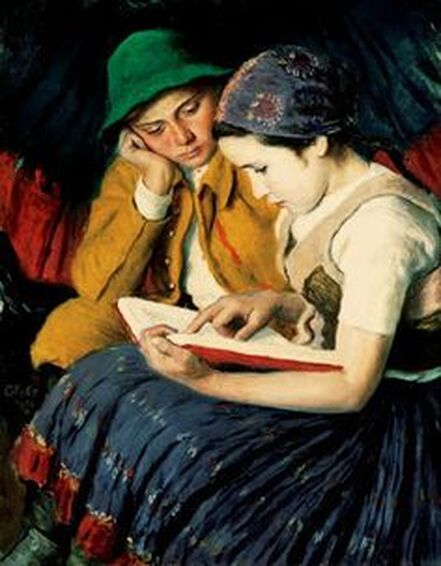

When asked whether the outgoing EC president considers Orbán a European leader, Juncker said, "He’s a Hungarian leader!” stating ”…his number one concern is his country, not Europe. And that is a huge mistake.” And if 'nationalist' leaders like Orbán are subdued and removed from power in the future, and the EU becomes the nationless superstate it wants to be, I suspect EU leaders will be criticized in the following manner: "He's a European leader! His number one concern is for Europe, not the World Government! And that is a huge mistake!" Note: Though it can serve as a temporary bulwark against the manifestation of a totalitarian one-world government, I do not believe nationalism alone can save any country, particularly in the West. I also think those working toward a totalitarian one-world government believe this as well, which is why they usually do not take extremely hard measures against nationalist sentiments when they appear. The Establishment know they can use nationalism to their advantage as well if need be. In the end, the only thing they would truly fear (and the only thing that would truly work against their plans) is a religious renaissance, which helps explain why the EU refused to even mention Christianity in its constitution and other founding documents. In my opinion, this painting succeeds in capturing the essence of artistic frustration - those agonizing times in a creative person's life when creativity simply refuses to click. It's too bad Borsos did not paint one called "Dissatisfied Writer." I imagine I would be quite drawn to a painting like that. It would perfectly reflect how I have felt about my own writing in the past few weeks.

Though my eleven-year stretch as a high school English teacher is speckled with some fond memories and bright moments, I would chalk up my overall experience of working as a secondary school educator as a negative one. Sure, I enjoyed working with some of the students and yes, ephemeral moments when it all seemed worthwhile did materialize from time to time, but the daily deluge of politically-inspired nonsense coupled with constant pressure of maintaining order and civility in places that seemingly inspired and incited chaos and incivility ensured those precious moments of meaning and contentment remained fleeting and assailable. Reflecting upon my time as a teacher inevitably conjures metaphors of suffering through a decade-long siege, one in which I wasted vast amounts of energy attempting to defend the indefensible. By the eleventh year I realized there could be no victory, and I fittingly laid down my arms and abandoned my post on the rampart.

Nevertheless, there are some things I keenly miss from those years, reading William Shakespeare on a daily basis being foremost among them. The works I covered in my classes rarely extended beyond the basic high school staples – Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, King Lear, occasionally Hamlet – but reading and discussing these plays for months at a time made the siege more bearable and helped mute the thunder made by the boulders perpetually pounding away at the fortress walls. Reading Shakespeare in class was akin to descending into the catacombs beneath the fortress; the discovery of a network of subterranean passageways and chambers that offered temporary reprieve from the never-ending battles raging above. Sitting huddled together, my students and I recited the Bard’s immortal lines to time while enveloped in the gentle profundity only the dead can offer. And hours afterward, the lines would remain with me – soft points of flickering candlelight that soothingly illuminated my mind and soul. Riding home on the 4 train in the afternoons absently staring out at the non-descript urban bleakness locals referred to as the South Bronx, I would silently recite entire scenes from Shakespeare to myself. This habit helped overpower the sinking feeling of futility that plagued most of my teaching days. As the Bard’s lines rolled through me, I would glance at my fellow passengers – at the glassy-eyed, the fatigued, the impervious – who, like me, had somehow made it through the day, but were already possessed by thoughts of to-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow as the train descended into dark bowels of Manhattan. Then one day, my to-morrows as a high school teacher suddenly became yesterdays. No, I don’t miss much from those times. Sure, they were necessary, and yes, the experiences I gathered were all obviously a part of my growth and development, and if I had to do it again, I could, but in the end I cannot in all sincerity say I miss much from those years, except for Shakespeare of course. My end as a high school teacher also marked the end of my daily engagement with Shakespeare. The other day, I realized it has been five years since I last read anything by the Bard, and I felt a sudden rush of inspiration to reengage with his work. This time, however, I vow to read him where he deserves to be read - in the full light of day under a vast expanse of sky well beyond the secretive confines of the catacombs that had sheltered and protected me from the siege and the unhealable damage it sought to inflict over the span of that most burdensome of decades. Laura Wood, who maintains The Thinking Housewife, has graciously included a post about my novel on her blog. The post was inspired by an email sent by Steeple Tea blogger S.K. Orr, who referred to The City of Earthly Desire in response to another post criticizing pornography.

A heartfelt thanks to Laura and S.K. for the interest they have shown in the novel. This evening my nearly eight-year-old son called me into his bedroom and informed me he would like to have a reading lamp placed next to his bed so that he can read every night before falling asleep. He then meticulously described how he we should rearrange the furniture in his room in order to make room for the lamp.

I never could have imagined that the mere thought of purchasing a lamp could bring so much joy! Oszkár Glatz (1872 - 1958) was a Hungarian painter whose life spanned one of the most tumultuous and unstable periods in Hungarian history. Born five years after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Glatz began life as citizen of an unsteady dual monarchy the Habsburgs hammered out after they quelled the unsuccessful Hungarian Revolution of 1848 that sought Magyar independence from Austria, only to see this political union evaporate immediately after the First World War. Austria-Hungary became the Hungarian People's Republic before Béla Kuhn successfully inspired a communist revolution that quickly ushered in the Hungarian Soviet Republic. In 1920, Kuhn's communist state crumbled under the backlash of a counterrevolution that saw the communists driven from power and the establishment of the Regency years under the leadership of Miklós Horthy. Hungary allied with Germany in the Second World War, but was occupied by Nazi forces who established a fascist government under the flag of the Arrow Cross Party after Hitler lost faith in Horthy in 1944. When the war ended, Hungary was under Soviet occupation and over the course of the next three years became a satellite state of the Soviet Union. Glatz's final years as an old man coincided with the so-called Stalinist years of 1949-1956, which were the most oppressive years Hungary experienced under communism. The communists succeeded in making life so unbearable that it inspired Hungarians to rise up against them in 1956. The uprising ultimately failed, but it opened the door to reforms and ushered in a more lenient form of communism in Hungary that eventually evolved into what became known as "goulash communism." Though Oszkár Glatz lived through a great deal of political instability, his art remained remarkably apolitical throughout the bulk of his life. Instead of becoming bogged down in politics, Glatz dedicated his creativity to depicting traditional Hungarian family and community scenes. Many modern people would consider his painting to be over-idealized, perhaps even kitschy, but in my mind Glatz's paintings, despite their obvious idealism, are respectable and charming representations of Beauty, Truth, and Goodness. What I admire most about his art is his ability to capture scenes from Hungarian rural life, scenes portraying the positive essence of relationships within families and communities. Looking at his paintings motivates one to think "now this is what family and friendships are all about." In a way, he is could be considered a Magyar Norman Rockwell. Oszkár Glatz was 74 years old when the transition to communism began in Hungary. He already had a long and relatively successful career behind him, a career in which he had avoided depicting the explicitly political in his painting. Of course, many would argue Glatz's idealized paintings of rural people and scenes contain an implicit political message, but for the sake of this post let us just assume he was aiming at representing nothing more than scenes from family life - that his intention was to represent loving relationships between family members. Had Glatz left his painting there, he would have remained an uncontroversial artist in Hungarian art history. But Glatz continued to paint during the transition to communism, and his painting from the 1950s reveal some perplexing choices. The painting below is called "Young Pioneer Visits Her Village Friends." (Young pioneers were essentially communist boy scouts and girl scouts although in terms of being ideologically driven, they were more along the lines of Germany's Hitlerjugend. For example, the communists routinely indoctrinated young pioneers to spy and inform on their families and neighbors). The painting below follows the same "formula" Glatz employs in so many of his other works, but his inclusion of the young pioneer girl disturbs the aura of Beauty, Truth, and Goodness Glatz had maintained throughout his earlier representations of simple rural life. Another painting, one depicting Hungarian young pioneers enthusiastically examining a globe with their North Korean communist peers, is pure Socialist Realism. Attempting to understand how an artist like Glatz became so enamoured with communism so late in life is difficult and perplexing. I have read that he became disillusioned with the traditional scenes he painted. I read elsewhere that he merely developed his family themes to the communist level of the universal proletariat family. Some sources claim he became a true believer. Others argue his communist paintings had more to do with expediency than ideology.

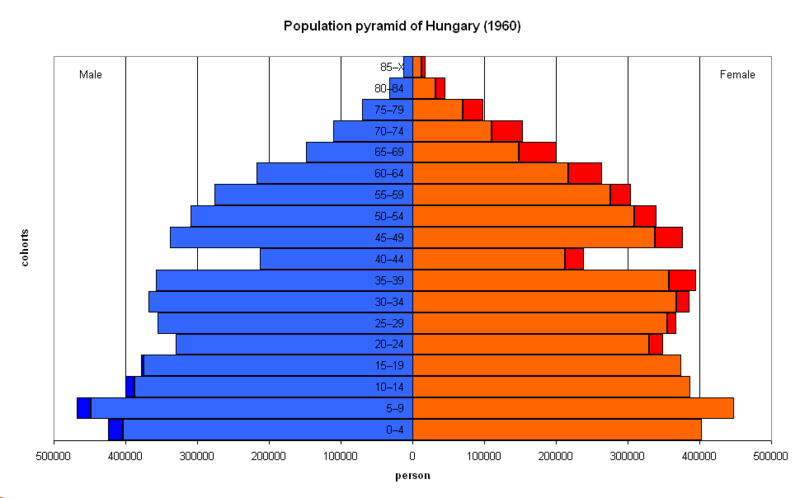

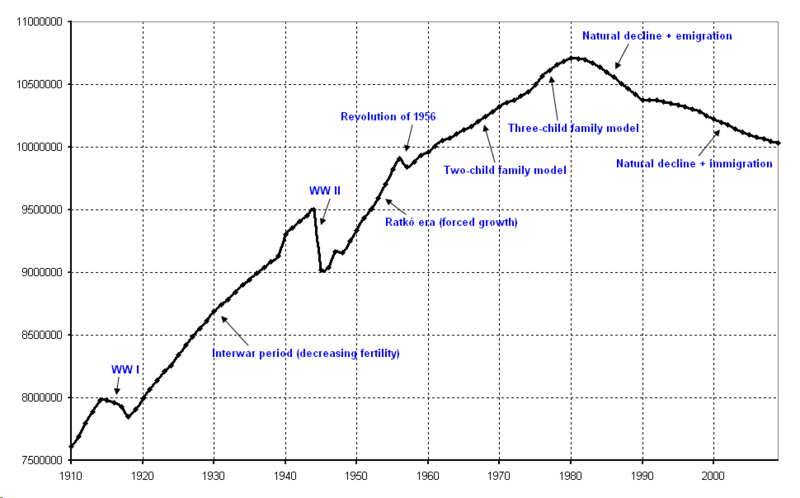

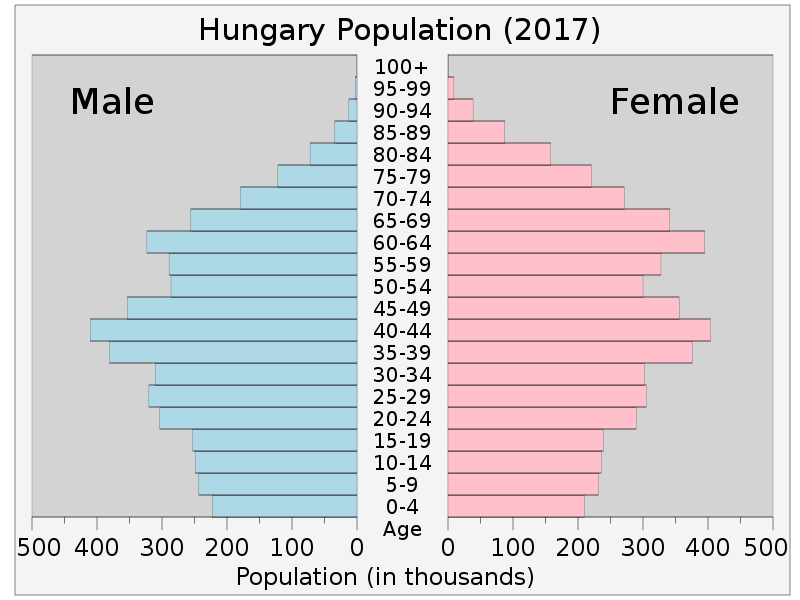

Whatever the case, somewhere in the late 1940s, when Glatz was already well into his seventies, he made a conscious decision to move away from the subject matter he had painted his entire life and begin painting idealized scenes of communist life. He was an octogenarian when he painted the scene with the young pioneer visiting her friends. Though some maintain Glatz had been more or less forced into shifting into communist themes, my intuition tells me his choice had been voluntary - that he honestly believed in the paradise communism professed to offer. If he hadn't, he would not have bothered to make the transition. After all, the communists permitted retirement, especially to people in their seventies and eighties - but Glatz chose to remain active. He could have put away his brush and hung up his apron and simply say he was too old and tired to paint anymore, but he didn't - and that, in my opinion, pretty much says it all. Hungary's history can best be summed up with one word - turbulent. This holds particularly true for the twentieth century, which was among the most chaotic the country had ever experienced. In the span of that particular one hundred years, Hungary lived through the First World War, territorial dismemberment resulting in a loss of about sixty percent of its former territory and about thirty percent of its population, a short-lived, but violent "Red Terror" communist regime under Béla Kuhn, a reactionary "White Terror" movement and the establishment of the Horthy regime, the Second World War, Nazi occupation followed by Soviet occupation, the worst hyperinflation in recorded history, a second and longer lasting communist regime, the collapse of that communist regime, and the ushering of Western liberal democracy. Simply put, most of the twentieth century for Hungary was characterized by little more than instability and disorder. Despite all the upheavals and uncertainties the twentieth century unleashed upon Hungary, the country's population increased for the bulk of those tempestuous one hundred years. As the graph illustrates, the upward trend in population growth from 1910 to 1960 is marred by three notable periods of decline – the First World War, the Second World War, and the failed Hungarian Revolution of 1956. These declines are a result of terrible military and civilian casualties suffered during times of armed conflict; however, on the graph they appear as blips in the overall upward trend of population growth. In other words, the country managed to recover from these catastrophic times and resume its upward population growth trend even against the backdrop of an underlying fertility rate decline that started shortly after the First World War. Hungary’s population eventually peaked at about 10.7 million in 1980 and was quickly followed by what appear to be irreversible declines in both the population and the fertility rate. Unlike the previous three dips in the overall population, the decrease that began in 1980 cannot be attributed to war or armed conflict, but rather to emigration and, more notably, a plummeting fertility rate. Though Hungary’s population continued to grow for much of the twentieth century in spite of many disasters and instabilities plaguing the century, the country’s fertility rate over the course of those ten decades reveals a significant downtrend. Hungary’s fertility rate was a remarkable 5.28 in 1900, but this dropped by roughly 1.0 per decade until 1930 when the rate settled at 2.84. Between 1930 and 1946 – a period that included the Great Depression and the Second World War – Hungary’s fertility bounced between 2.5 and 2.8. Although these numbers are half of what they were at the beginning of the century, they are still above the minimum 2.1 figure required to ensure population replacement, which in turn helps explain why Hungary’s population continued to grow despite the falling fertility rate and the sizable casualties the Second World War had inflicted upon the country. The fertility rate managed to remain above sub-replacement even in 1946-47, which marked the worst case of hyperinflation in recorded history, Much of the decline Hungary's fertility rate between 1900 and 1946 can be attributed to conventional factors such as urbanization and the changing role of women in society, but the slow and steady weakening of the traditional Christian family and social framework that had dominated Hungarian society since its inception certainly played a role as well. Although fertility rates dropped rather drastically in the first half of the twentieth century, Hungarians maintained some semblance societal health by upholding a fertility rate that exceeded replacement levels. The waning of Christian social norms in the first half of the century were ground into the dirt when the communists seized control of Hungary in 1946. The communists officially suppressed and controlled religion within Hungary. They openly mocked any mention of the metaphysical, made a hobby of rounding up and imprisoning the clergy, and worked tirelessly to establish a purely materialistic dictatorship of the proletariat within the country’s borders. The first decade of communist rule was particularly violent and oppressive, which caused the fertility rate to continue its decline. However, it remained above replacement levels despite all the turmoil and uncertainty the communists induced within the country. For example in 1956, the year marking the failed Hungarian uprising against the communist regime, the fertility rate in Hungary was still slightly above replacement levels at 2.44 . Although the revolt against the communists ultimately failed, it did succeed in loosening communism's iron grip somewhat. True, Hungarians remained oppressed, but they were not as oppressed as they had been before 1956. Nevertheless, Moscow’s attempts to provide the nation with a kinder, gentler version of communism – one emphasizing increased material comfort, social stability, and slight increases in personal freedoms – did nothing to improve the fertility rate, which sank to below replacement levels for first time in Hungary’s recorded history. I surmise the unprecedented 2.02 sub-fertility rate recorded in 1960 had much to do with the despair communism induced in the general population. Though the country maintained acceptable standards of living from a historical perspective, Marx’s promise of utopia showed little signs of materializing. Communism may have provided enough to live on, but it provided little to live for. Unsurprisingly, alcoholism and suicide rates rose as the fertility rate continued to fall. By the early 1970s, Hungary’s fertility rate had cracked below 2.0, prompting the communists to begin pushing a three child policy to increase fertility among the population. Amazingly, the social schemes the communists promulgated had an immediate and positive effect on the fertility rate, which quickly jumped above sub-replacement levels again and remained above sub-replacement levels for the better part of four years. However, the boost the communist family schemes provided proved to be the equivalent of a sugar high – they gave a quick burst of energy, but lacked the nourishment required to make the social engineering sustainable. By 1978, the fertility rate was back below replacement levels again at 2.08, despite the communist's desperate efforts to counteract it, remained below replacement levels for the remainder of their time in power. Hungary’s population peaked in 1980, which was around the same time communism peaked. Though it would take another nine years to officially collapse, communism in Hungary grew observably weak and fatigued in the 1980s; yet this political devitalization did little to revitalize the country’s fertility rate. On the contrary, the more liberal and laissez-faire the communists became, the more the fertility rate fell. After 1980, the rate dropped to below 2.0. By the time the Iron Curtain came down, Hungary’s fertility rate was a pathetic 1.78. When the Iron Curtain was dismantled, Hungary became part of the liberal West. After nearly fifty years of political oppression and despair, the country hungered for the personal freedoms and material prosperity Western liberalism offered. It certainly was an optimistic time, and one would assume rejoining the West would have an overall positive effect on the country’s fertility rate, and for a few short years it did. Coinciding with the hope inspired by rejoining the West, Hungary’s fertility rate climbed slightly in the early 1990’s, but by 1999 it nosedived all the way down to 1.29 and remained at those abysmal levels all the way to 2011 when it sank to 1.23, which is the lowest recorded fertility level in Hungarian history. If nothing else, fertility rate statistics reveal Hungary’s response to communism had been despairing and suicidal. Nevertheless, these stats also show Hungary’s response to Western liberalism after the fall of the Iron Curtain has been even more despairing and suicidal. Though sub-fertility stains both periods, the numbers show Hungarians chose to have more children under communist oppression than they do in the apparent freedom of Western liberalism. As pernicious as communism was, it appears to have been less despair-inducing and suicidal than Western liberalism has been in Hungary - at least as far as fertility rates and societal health are concerned. Of course, communism and liberalism are both forms of Leftism. Taken together, it is quite apparent that both are detrimental to a country’s fertility rate and overall demographics, which is hardly surprising considering the basic tenets of Leftism. All the same, it is rather startling to discover that liberalism, which is touted for its apparent love of freedom, tolerance, and human rights, is far more despair-inducing and suicidal in demographic terms than communism ever was. As unbelievable as it seems, Hungary's immersion into Western liberalism only exacerbated the demographic malaise communism had initiated in the second half of the twentieth century. Surprisingly, Hungary’s fertility rate has experienced a slow but steady increase this decade. The fertility rate has risen nearly every year since the 1.23 trough set in 2011 and now sits at 1.49. Though the figure is still paltry, this minor turnaround could be attributed to Viktor Orbán and his push to make Hungary an “illiberal democracy.” Recognizing the suicidal path the country had been on, Orbán's government has launched a massive campaign to increase the fertility rate to above replacement levels. The actions the government has taken appear to be having positive effects. Marriage rates are rising and fertility levels remain stable. Nonetheless, it is too soon to know if Orbán’s well-intentioned schemes will bear fruit. After all, the communists initiated similar policies in the 1970s, but the positive outcomes their policies produced were incredibly short-lived. When all is said and done, I fear Orbán’s policies might suffer a similar fate unless the real root of the demographic problem is dealt with. The communists saw sub-replacement fertility as a material problem. As such, the remedies they offered were also of a material nature. Unsurprisingly, these material solutions did nothing to address the underlying immaterial cause of the problem, which was spiritual in nature. Orbán also recognizes the material dangers of sub-fertility. Like the communists in the 1970s, he is attempting to counteract the low fertility rate by offering material solutions. However, unlike the communists, Orbán seems to understand the root of the problem is spiritual in nature, which helps explain why he often praises Christianity and lauds the necessity of Christian values. Orbán may understand the root of the sub-fertility catastrophe is spiritual in nature, but the million dollar question is this - Do contemporary Hungarians understand this as well? If they do, Orbán’s admirable attempts at reversing the decline in fertility stand a chance. If not, Orbán’s family support schemes will inevitably meet the same fate the communist schemes of the 1970s did. If history is any guide, material provisions alone will not aid the fertility rate and may actually cause more harm than good in the long term. The only solution to sub-replacement fertility - in Hungary or any other Western country for that matter - is spiritual reawakening. Anything less will only serve to accelerate or prolong the despair-induced demographic suicide plaguing Hungary and the West. The two population pyramids below illustrate the gravity of the problem in contemporary Hungary and highlight Western liberalism's exacerbation of the demographic dilemma the communists had inadvertently initiated in the mid-twentieth century. As bad as communism was for Hungary's demography and fertility, Western liberalism has been undeniably worse.  |

Blog and Comments

Blog posts tend to be spontaneous, unpolished, first draft entries ranging from the insightful and periodically profound to the poorly-argued and occasionally disparaging. Comments are welcome but moderated. Please use your name or a pseudonym in comments. Attempts at prolonged, pointless, time-wasting comment debates are regarded with strong disdain. Emails welcome: f er en c ber g er (at) h otm ail (dot) co m Blogs/Sites I Read

Bruce Charlton's Notions Meeting the Masters From The Narrow Desert Synlogos ✞ Aggregator New World Island New World Island YouTube Steeple Tea Adam Piggott Fourth Gospel Blog The Orthosphere Junior Ganymede Trees and Triads nicholasberdyaev Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed