After sentencing they put me into a car with screened windows. They drove around for more than two hours while I was sitting between two armed prison guards. I thought I was transported to the city of Szeged, but as it turned out they carried me only to another prison in Budapest, about 10 minutes from the courthouse.

For almost three years I lived in this prison, the prison of Konti Street. I was in utter solitude, never meeting anyone. I was one of the so-called “secret prisoners.” As I learned later, there were two other such prisoners there: Msgr. Grösz, the archbishop of Kalocsa, and the former Socialist leader, Arpád Szakasits.

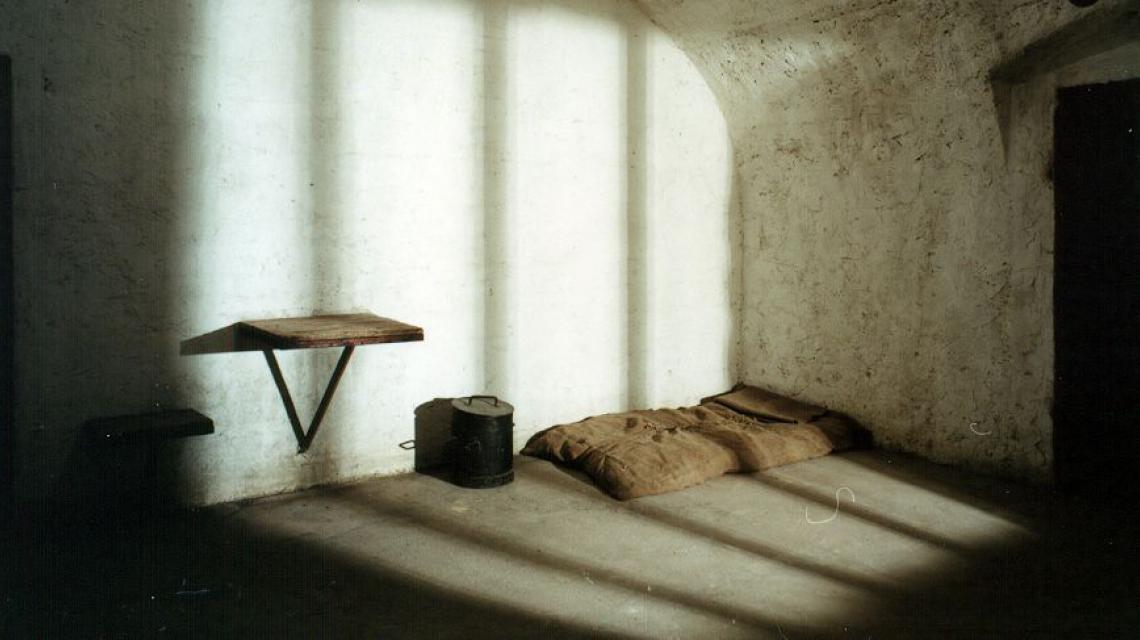

In this prison the guards made me suffer a great deal. Often they did not let me out to the restroom. For hours I was in extreme pain. My cell was filthy, my skin was infected in the dirty cell, three times my face was disfigured by such infections. They fed me with bread made of flour gone bad. But during the winter they heated rather well. Each pair of cells had a common stove.

The day after my arrest I petitioned that I be allowed to say mass. First at Christmas of 1950 then at Easter of 1951 I was given permission to celebrate mass. But only from May 3, 1951, Ascension Thursday, did I receive a chance to say mass daily. They brought to my cell a chalice broken at its handle (I had to fix it with a piece of string) and a Franciscan mass book. Through five and a half years I was able to celebrate mass each day. At Christmas and All Souls’ Day I said three masses. At the beginning they tried to mock me while I was saying mass. But when they saw that I was not paying attention to them, they stopped. From the beginning of my imprisonment I asked for an opportunity to go to confession. I sent letters to the Ministry of Justice with this request but never received an answer.

Otherwise, I did everything to stay busy, keep my mind occupied. Whatever was beautiful in my life, I tried to recall over and over. In this way God’s grace had been doubled in my soul and comforted me in my prison life.

On August 7, 1953, the feast of St. Cajetan, I had my first chance to go out for a walk. One round in the courtyard took 68 steps. I was allowed 12 rounds. Later, my walks were made longer. In the prison to which I was later transferred, I was allowed to walk twice a day. There I was able to stay in the sun, sometimes even to sit down. In 1954 or 1955, in the summer, I ventured to stop, admiring a little piece of weed. The guard urged me in a rude voice: keep on walking!

For the first eight months of my imprisonment I received no books, no paper and pencil or pen. After my sentencing I received numbered sheets of paper, the guards repeatedly checked what I was writing down. I was solving math problems and made notes of the books I was given to read. The prison library consisted mostly of Soviet authors. I read Gorky, Ilya Ehrenburg and others. The rest of the books were atheistic, hateful toward church and clergy and showing employers in the worst light.

A few days before my sentencing, I was offered a chance to request other books. I asked for a Bible, the book Canon Law for Religious Orders, and a book on math or physics. The first two titles were immediately rejected, a book on math and physics was delivered into my hands five years later, on November 1, 1956, the day of my liberation by the freedom fighters. But two months after my trial I received the four volumes of the Breviary. And right after sentencing they gave me a rosary, though not my own.

Throughout the prison years I had to get up at 5:30 AM. The routine consisted of washing, dressing and cleaning the cells. Breakfast was given at 8 AM. In the first years, for breakfast they gave us soup cooked with shortening and flower, later they switched to the black coffee used by the military.8 They gave each day 300 grams of bread (2/3 of a pound), in three allotments. Lunch was given at 12 noon; it consisted of soup (made of canned vegetables) and about half a liter of some cooked vegetables. Once a week 100 grams of boiled meat was offered; on Saturday and Sunday the dinner was cold cuts. At 9 PM we had to go to bed. But in the year of 1956 my food was identical with that of the prison personnel.

In my first prison (Konti Street) I was given a numbered metal bowl and a spoon with the same number on it. The number was 201. When they moved me to another prison, the bowl and the spoon accompanied me so that I would not attempt sending any message of my whereabouts in the way customary among political prisoners.

Right after my arrest there was no heating in the cells in which I stayed, only the hallways were kept warm and from there we received some heat. By the way, underground cells are usually not very cold, only extremely dirty and stinking. The Konti-Street prison was adequately warm. But in Vác, my next prison where I spent almost two years, there was no heating whatsoever. It was there that each finger on both my hands, three toes on my right foot and two on the left as well as my left ear were frozen.

I was otherwise never seriously sick, but I went through the usual prisoner illnesses. I struggled with infections of the digestive system, lack of vitamin C, my teeth became loose, many broke or fell out. I had problems with my sense of balance (inner ear), deficiencies of the heart and sleeplessness.

But my nerves did not give up and I preserved my sense of humor. I was able to rejoice seeing a small bunch of weeds pushing its leaves up in the prison court. I have put its leaves into my breviary; I still keep them.

When I was sick with those “prison illnesses,” doctors of the secret police came to take care of me; their behavior and treatment was impeccable. To such secret prisoners as me, the regular prison doctors were not allowed. The prison cells of the secret police and the restrooms were horribly dirty. They did not clean them, nor did they give cleaning instruments for us to clean them. It was only in the prison on Konti Street that I got for the first time a separate towel, a piece of soap, a wash bowl. There I could treat the floor with oil and keep it cleaner. In the prison of Vác there were countless bedbugs in my cell. On the first three days after my arrival, May 13, 1954, I killed 750 of them. Later I got some DDT in powder and I was able to get rid of them all. In other prisons I found no bugs.

It was like a blessing to get from Vác to my last prison, the Central Prison in Budapest. It happened on Good Friday, March 30, 1956. They placed me in the same cell in which, as I later learned, Cardinal Mindszenty had spent quite some time. Although I was still isolated from everyone, life became much more bearable. I was given paper, pencil and books to read.

About the attitude of my guards working for the secret police, I have already spoken. In the prison on Konti Street they at times turned on the lights 30 times during a single night so that the prisoner would not have a chance to sleep. It was most terrible to hear them blaspheme the name of God, the Lord Jesus and the Virgin Mary in the context of incredible obscenities. But I met some more humane guards even at the worst places.

I had a cellmate only during the first months of my imprisonment, while preparing for the trial. I thought, at first, that they were snitches working for the police. My first companion came in January of 1951, he was a former general of the Army. He greeted me with the words: “Please don’t tell a thing about yourself.” I thought from this that he cannot be an agent. Later a captain of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, then another colonel of the Army, an engineer, were my companions. But for the next six years I was completely alone.

Throughout these years I had one single visit. Three months before being set free, my brother’s son was allowed to see me. We were allowed to speak to each other for half an hour. It was from him that I learned that on January 16, my mother had died. It was at that time that I also learned about the death of a member of our Abbey, Fr. Justin Baranyai. It hurt me so much to learn that in the prison he had lost his mind and never recovered, even after he had been set free.

When I was freed*, my original clothes in which I had been arrested could not be found. They only found my watch tied to shoelaces; they returned my abbatial ring and a clergy suite.

My life of six years in prison is an asset which I would not exchange for any earthly treasure. By all this, my life was enriched by an incredible extra value. I feel no anger against any person who tortured me.

*As noted earlier in the excerpt, Endrédy was freed by Hungarian freedom fighters during the short-lived 1956 Hungarian Revolution. He was re-arrested after the failed uprising and served out the remainder of his 14-year sentence in a care home for retired clergy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed