After I had watched the film in the nineties, I attempted to read Welsh’s novel upon which the movie is based, but I could not make it past the first thirty or forty pages. Unlike other readers who abandon Welsh’s fiction a few chapters into a novel, I was not put off by the Edinburgh vernacular slang style Welsh employs, but the bleak brutality of Welsh’s nihilistic vision.

I once read a newspaper article or review which stated Welsh is obsessed with teleology and that his novels are all essentially teleological experiments in which Welsh explores the dark and desperate side of the human condition in an effort to find his characters’ ultimate purpose in life – their intrinsic telos. Though this sounds immensely noble, I do not believe Welsh has succeeded in finding any explanations for any of his characters’ goals or ends.

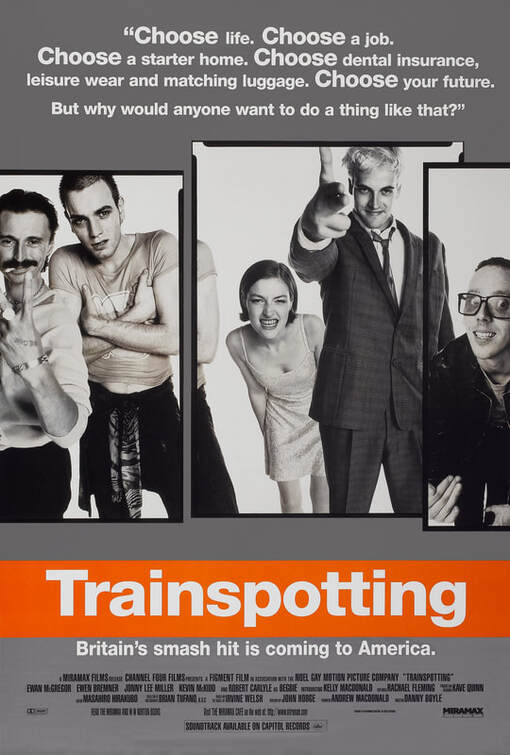

Like so many contemporary writers, Irvine Welsh gets what the problem of human life in the modern world is. This is nowhere more apparent than in the now famous “Choose Life” monologue the protagonist Mark Renton rifles off at the beginning of the film adaptation of Trainspotting. (The monologue in the novel differs slightly, but the message is essentially the same):

“Choose Life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fucking big television, choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players and electrical tin openers. Choose good health, low cholesterol, and dental insurance. Choose fixed interest mortgage repayments. Choose a starter home. Choose your friends. Choose leisurewear and matching luggage. Choose a three-piece suit on hire purchase in a range of fucking fabrics. Choose DIY and wondering who the fuck you are on Sunday morning. Choose sitting on that couch watching mind-numbing, spirit-crushing game shows, stuffing fucking junk food into your mouth. Choose rotting away at the end of it all, pissing your last in a miserable home, nothing more than an embarrassment to the selfish, fucked up brats you spawned to replace yourselves. Choose your future. Choose life… But why would I want to do a thing like that? I chose not to choose life. I chose somethin’ else. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who needs reasons when you’ve got heroin?”

As mentioned above, Welsh clearly sees where the problems of modern life lie – materialism, mass consumerism, financial slavery, mass media addiction, alienation, aimlessness – but like so many other contemporary writers, Welsh refuses to acknowledge or accept the only antidote to the nihilistic wasteland he so poignantly recognizes and identifies. This is what made Trainspotting such a depressing film in the end.

The hapless characters try to escape their despair through heroin, which inevitable only deepens their despair. The protagonist, Renton, eventually overcomes his addiction, betrays his friends, and steals money from a drug deal in an effort to redeem himself and relaunch his life. Yet what does he ultimately choose? He Chooses Life. The job. The career. The washing machines and all the rest of it. In other words, Renton goes full circle and ends up fully embracing the materialistic nightmare he had spent the vast majority of the film trying to escape through drugs.

To me, this reveals Welsh either does not understand Reality or is openly antagonistic toward any notion of Reality. And this is not simply a case of an author creating characters who do not reflect the author’s actual worldview. When I watched Trainspotting and read what little I did of the novel, it became quite clear, at least to me, that Welsh’s characters are essentially mouthpieces of Welsh’s outlook on life, as the following excerpt from Trainspotting (the novel) demonstrates:

“Ah don’t really know, Tam, ah jist dinnae. It kinday makes things seem mair real tae us. Life’s boring and futile. We start aof wi high hopes, then we bottle it. We realise that we’re aw gaunnae die, withoot really findin oot the big answers. We develop aw they long-winded ideas which just interpret the reality ay oor lives in different weys, withoot really extending oor body ay worthwhile knowledge, about the big things, the real things. Basically, we live a short, disappointing life; and then we die. We fill up oor lives wi shite, things like careers and relationships tae delude oorsels that it isnae totally pointless. Smack’s an honest drug, because it strips away these delusions. Wi smack, whin ye feel good, ye feel immortal. Whin ye feel bad, it intensifies the shite that’s already thair. It’s the only really honest drug. It doesnae alter yer consciousness. It just gies ye a hit and a sense ay well-being. Eftir that, ye see the misery ay the world as it is, and ye cannae anaesthetise yirsel against it.”

As much as I enjoyed the film, the “resolution” Welsh’s story offers at the end is no resolution all. Deep down, Welsh seems to recognize this – knows it is a cop-out – but it is the only resolution he is willing to provide because he is utterly hostile to the only real resolution.

Hence, there are no answers, at least none worth considering. When Renton grins at the end of the film and happily claims to be Choosing Life, he is ultimately Choosing Death, and that is what makes Irvine Welsh’s vision of life – a vision of nothingness – so terribly saddening and, ultimately, unsatisfying.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed