I'll try to explain in the following. Bear with me:

In Ressentiment, Max Scheler juxtaposes ancient and Christian views of love to help clarify and define the unique qualities of Christian love.

According to Scheler, the most important difference between ancient and Christian conceptualizations of love lies in the direction of its movement. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers and poets deemed the essence of love to be an upward striving – a movement of aspiration of the lower, weaker, ignorant, and less-formed toward the higher, stronger, wiser, and more-formed.

This upward movement of love is clearly expressed in all life relations in antiquity, including marriage, friendship, and social relations. It made clear distinctions between the “lover” and the “beloved”, with the former being the lower striver and the latter being the higher who is striven after.

It finds its most lucid expression in Greek metaphysics, in which the most perfect form becomes the pinnacle of love that can experience no aspiration, striving, or need. Instead, the most perfect form becomes the prime mover who does not move but attracts, entices, and tempts other beings toward it.

Thus, the essence of the ancient conception of love results in a great chain of dynamic spiritual entities all striving upward but never looking back. The process continues all the way to the deity, which does not love but represents the eternally unmoving and unifying goal of all aspirations of love.

Within this framework, love is only a dynamic means through which to achieve an ultimate, static goal. From a different perspective, using the means of love, the ancients strove to attain the end of not having to love at all but instead become the ultimate principle that attracts all other love. Within this perpetual striving upward, the ancient Greeks regarded love to be a limited commodity that needed to be invested wisely and not wasted by condescending to the lower.

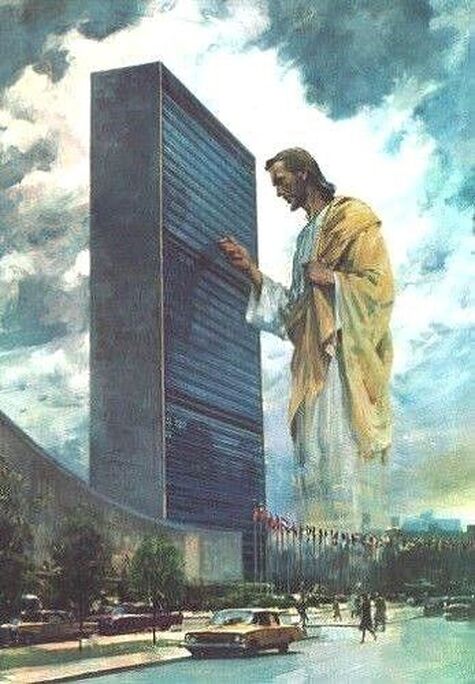

Scheler observes that the Christian view of love turns the ancient Greek axiom on its head. Instead of the lower aspiring toward the higher, the Christian criterion of love has the higher stooping toward the lower, the wise to the ignorant, the rich to the poor, and so forth.

Scheler notes that the Christian, unlike the ancient Greek, suffers no anxiety that he loses something in the process of looking back or looking below. On the contrary, the Christian harbors the pious conviction that his act of descending toward the lower not only ennobles him but that it earns him the highest good because it makes him equal to God – at least in action.

For the Christian, God ceases to be the eternal unmoving star beckoning all life toward it like a beloved beckoning the lover and becomes instead a “creator” who creates “out of love”. The essence of the Christian God is to love and to serve through acting, thinking, and creating. The highest good for a Christian does not involve aspiring toward the prime mover who does not love but to align with the act and movement of Divine Love itself. Love itself and actively participating in the continuing expansion of love becomes a Christian’s highest good. Scheler writes:

The summum bonum is no longer the value of a thing, but of an act, the value of love itself as love—not for its results and achievements. Indeed, the achievements of love are only symbols and proofs of its presence in the person. And thus God himself becomes a “person” who has no “idea of the good,” no “form and order,” no logos above him, but only below him—through his deed of love.

He becomes a God who loves—for the man of antiquity something like a square circle, an “imperfect perfection.” How strongly did Neo-Platonic criticism stress that love is a form of “need” and “aspiration” which indicates “imperfection,” and that it is false, presumptuous, and sinful to attribute it to the deity!

But there is another great innovation: in the Christian view, love is a non-sensuous act of the spirit (not a mere state of feeling, as for the moderns), but it is nevertheless not a striving and desiring, and even less a need. These acts consume themselves in the realization of the desired goal. Love, however, grows in its action. And there are no longer any rational principles, any rules or justice, higher than love, independent of it and preceding it, which should guide its action and its distribution among men according to their value. All are worthy of love—friends and enemies, the good and the evil, the noble and the common.

Scheler defines the above as authentic Christian love. As such, he declares it to be free of ressentiment (resentment). Nevertheless, he is quick to admit that ressentiment can taint Christian love and subtly hijack it for its own purposes, most notably in pursuits like altruism.

Scheler chalked up the difference between ancient and Christian views of love to the direction of its movement. Another possible way to conceptualize this is to consider the direction of movement as participation – the way in which men choose to take part, cooperate, and play a part in Creation. For the ancients, participation was largely a matter of using love to strive upward toward the goal of the unmoved mover who attracts all love but is attracted to nothing and loves nothing.

For Christians, participation seems to be more a matter of loving and cooperating with a personal Creator who also loves. The only “end” so to speak is the expansion of love, through which Creation itself expands.

Unlike the ancient deity, the Christian God actively desires that the lower become higher. Creation itself becomes a place in which to “raise up” gods. However, this raising up does not involve God attracting. On the contrary, in Creation, God enables this “raising up” by “condescending” to the lower, the weaker, and the unformed through love. Also unlike the ancient deity, the Christian God invites His believers to do the same because, contrary to what the ancients believed, such actions expand love and Creation rather than diminish it.

To sum up, becoming like God meant something very different to the ancients than it does for Christians. For the ancients, becoming god-like entailed a perpetual striving upward in which love must always be aimed at something higher and never at anything lower.

The case is the opposite with Christian love where Divine Love freely and willingly condescends to work creatively with the lower to expand love within Creation.

Becoming god-like in Christianity involves participating in that Divine Love by treating love as a never-ending dynamic end rather than as a dynamic means through which to attain a static end. The god of the ancients was an unmoving idol; the Christian God is a loving parent.

Note added: Scheler wrote Ressentiment from a primarily Roman Catholic perspective, yet he was able to detect and pierce the strains of classical philosophy that had flowed into Christian thinking over the centuries.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed