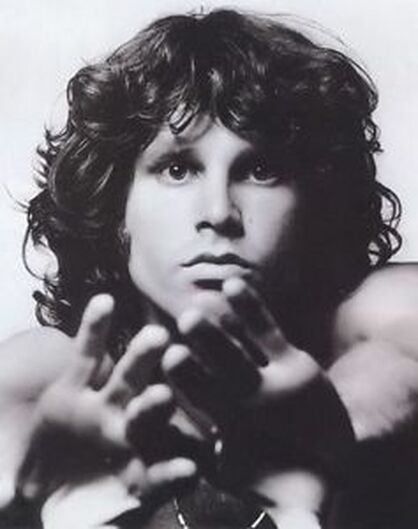

Though I had rejected my Catholic faith, I still believed in God and still possessed some form of spiritual yearning. I began seeking alternative approaches to the divine, and because I was sixteen, popular music was one of the first places I looked. The Doors was the first band to pique my interest in this regard. In one respect, the rock band was simply one of dozens that had exploded onto the scene at the height of the flower-power/hippie/sexual revolution era of the late-sixties. What set The Doors apart for me was the dark charisma of the band's lead singer, Jim Morrison.

Though I liked the band’s music, I felt a greater attraction to Morrison’s shamanistic persona and mystical lyrics. I immediately investigated the origin of the band’s name and discovered it had its source in a line from William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell:

"If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.”

Aldous Huxley took the title for his book The Doors of Perception, which details his attempt at psychedelic consciousness expansion via mescaline, from this line. In turn, Jim Morrison reduced the phrase even further by naming his rock-and-roll band The Doors after Huxley's book. At the age of sixteen, I considered all of this to be profound, and thus began my nearly three-year obsession with the life and work of James Douglas Morrison.

Looking back at it now, I realize what had fascinated me about Morrison was the dark spirituality he seemed to epitomize. Having turned my back on Catholicism, I was searching for another route toward the spiritual and, as silly as it sounds now, I was hopeful Jim Morrison could provide such a route.

In Morrison, I saw a kindred spirit who had an innate interest in consciousness. Like me, he had been a shy, sensitive youth drawn to poetry and literature. Like me, he sensed there was more to life than the material and had a keen interest in peak experiences and creative transcendence within which he believed the secret to life could be discovered. While other bands and singers of the era sang of incense and peppermints, Morrison crooned about breaking through the other side. His persona represented a raw, intense form of unbridled yearning for greater consciousness and experience that found no solace within conventional spiritual frameworks.

After reading No One Here Gets Out Alive by Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman, I regarded Morrison as an incarnated version of one of The Doors’ own songs - a wild child, full of grace, who offered the potential to be the savior of the human race. According to the biography, Morrison detested his lionization as a rock star and regarded his rocket ride to fame as a trap, one that kept him from pursuing his true calling as a poet and visionary. I took Morrison’s lack of interest in his eventual fame and material success as proof of the man’s dedication to higher things.

While the rest of his bandmates simply wanted to put on a show, Morrison aspired to elevate the crowd into a mass trance of transcendence with himself at the helm as the grand shaman. He began to mock his own celebrity altering the charismatic appearance that had made him a star. He grew a beard, gained weight, and began performing lewd and unpredictable antics on stage. Caught in a monster of his own making, he sought escape through alcohol and drugs, and his overindulgence eventually resulted in his premature death at the tender age of twenty-seven.

Convinced Morrison had been on to something, I spent a little over two years researching his life and work. I analyzed the lyrics to every Doors song, read every poem Morrison had written, and scoured countless secondary sources written by people ranging from his family members and associates to hardcore fans and academics. In 1990, I even made a pilgrimage to Mr. Mojo Risin’s grave in the Pere Lachaise cemetery in France.

What did I discover after my exhaustive research?

Well, nothing good.

The more I waded in Jim Morrison’s life, the more I realized he had been, at best, a minor mystic, but even that may a generous overestimation. In the end, I concluded Jim Morrison had been merely an intelligent and sensitive young man – an unexceptional poetic talent bolstered by exceptional charisma and stage presence who, rather tragically, happened to be in the right place doing the right thing when the tumultuous wave that was the 1960s deluged the world.

It did not take me long to realize that Morrison’s inherent spirituality was, at its core, quite base and material. Though he shared some brilliant observations during interviews and in some snippets of his poems and songs, Morrison’s spiritual insights rarely rose above the physical plane. Excess paved the road to wisdom, mystical experiences were the result of sex or drugs, and doors stood between the known and the unknown, but Morrison himself could offer no explicit revelation about what the unknown encompassed. Morrison obsessed with breaking through to the other side, but had been utterly indifferent to what the other side might actually contain.

Having written the above, I do believe Morrison possessed some level of spiritual intuition and occasional, non-drug induced moments of heightened awareness or consciousness, but I surmise he had no proper channels into which to funnel these. Rejecting Christianity, and every other religious tradition for that matter, Morrison directed his inherent, malformed spiritual energies in the only direction available to him – the tempestuous, chaotic, hedonistic 1960s counterculture he ironically professed to loathe.

The meeting of these two forces proved to be short-lived and fatal. When his divine spark encountered the noxious, combustible fumes of 1960s, it resulted in a horrendous and tragic spiritual backfire. Embracing the sexual revolution and drug culture with open arms, Morrison embarked on a truly spectacular and pointless five-year journey of self-destruction that culminated in his mysterious death in a Paris hotel room in 1971.

My interest in Jim Morrison waned after I turned nineteen. I continued my wayward spiritual quest in the works of Colin Wilson and P.D. Ouspensky and let Jim Morrison fade into the background. Though I still enjoy some of The Doors’ music whenever it comes on, I rarely think about the band or their tragic lead singer these days. I am certain my exposure to The Doors and Morrison was harmful to some degree, but with the exception of a few youthful drinking binges, I knew better than to follow Morrison down the paved road of excess in the hope of finding wisdom. Even as a teenager, I was averse to the idea of consciousness expansion through chemical means, and though I had turned away from the Catholic Church, it did not take me long to understand that the rock-and-roll, Lizard King shamanism Morrison offered was spiritual dead end that offered nothing more than an excuse for destructive, hedonistic indulgence.

Whenever I do think about Jim Morrison these days, it is from a speculative perspective. I imagine Jim Morrison would have made a formidable Christian had he chosen the path, and I wonder why he had seen no appeal in Christianity. Christ’s gift – the one and only true way to the other side - offers exactly what Morrison had longed for during life. All the right ingredients had been in place. Yet Morrison adhered to a hedonistic and rebellious worldview instead, which led to him a true Roman wilderness of pain, suffering, and early death. Though he had annagramatized his name to Mr Mojo Risin in the song L.A. Woman, Morrison had shown no real interest at the prospect of rising after death.

Sadly, his desire to break on through to the other side ended with a spiritual thud. I say this not from a position of judgmental scorn, but rather with a saddened heart. Say what you will about the man (and this despite the ample conspiracy theories about his being an agent of the establishment), I consider Jim Morrison to have been misguided rather than evil, and I cannot help but wonder what might have been had he seen the light in his own lifetime.

In 1990, his father had a flat stone placed on Morrison’s grave in Pere Lachaise. The bronze plaque on the stone contains the following inscription in Greek: ΚΑΤΑ ΤΟΝ ΔΑΙΜΟΝΑ ΕΑΥΤΟΥ.

This translates as "true to his own spirit" or "according to his own daemon.”

The second translation is more fitting in my opinion. It captures the tragedy of Jim Morrison and the lost spiritual potential he epitomized, a potential to which he himself was utterly oblivious as this short interview snippet, recorded less than a year before his death, clearly demonstrates.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed