Of course, nearly everyone who has read The Great Gatsby would argue the green light at the end of Daisy's dock is the most memorable symbol Fitzgerald weaves into his tragic narrative of ambition and yearning. I do not object to this because as the central symbol of the narrative, the green light is indeed the most memorable and is excellent within its own right. But the eyes of T.J. Eckleburg contains a haunting element the green light lacks - the brooding gaze of God, unceremoniously abandoned and virtually forgotten, staring out over a landscape marred by the spent debris of the greed, lust, and hedonism that have taken His place.

The eyes of T.J. Eckleburg make their first appearance in Chapter 2 when Nick accompanies Tom to the valley of ashes:

About half way between West Egg and New York the motor-road hastily joins the railroad and runs beside it for a quarter of a mile, so as to shrink away from a certain desolate area of land. This is a valley of ashes—a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air. Occasionally a line of grey cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-grey men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud which screens their obscure operations from your sight.

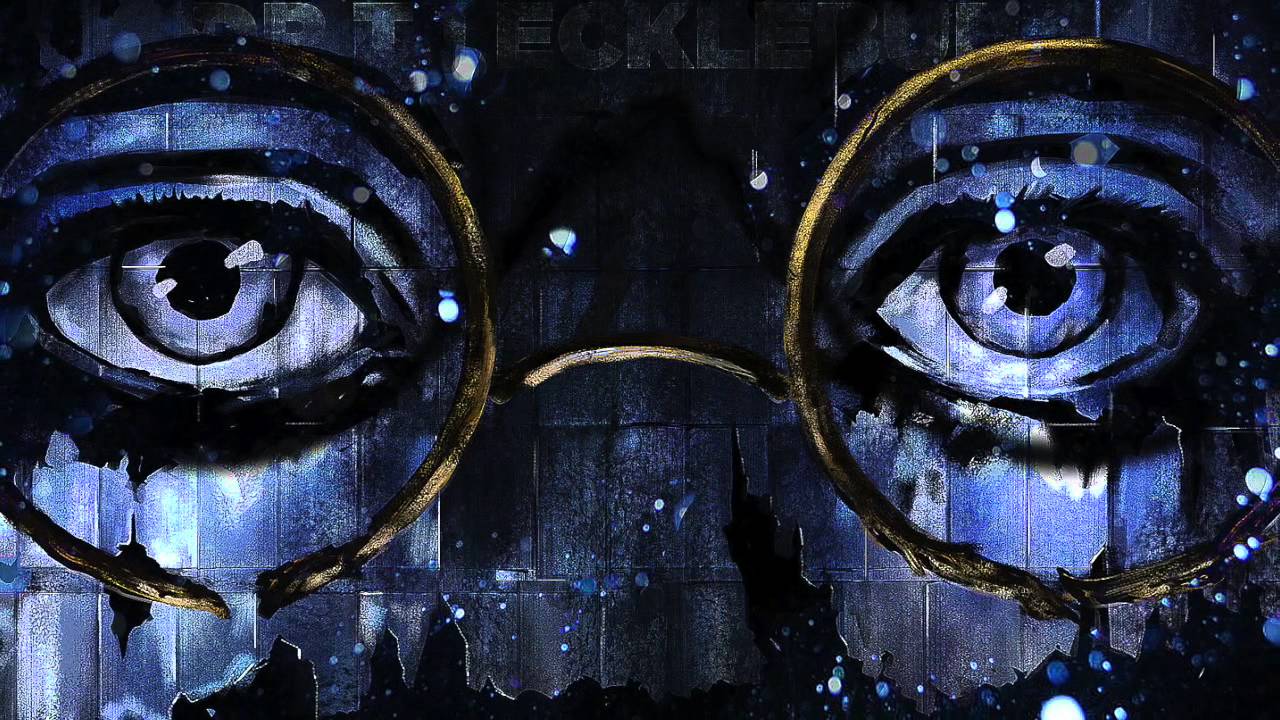

But above the grey land and the spasms of bleak dust which drift endlessly over it, you perceive, after a moment, the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg. The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a nonexistent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness or forgot them and moved away. But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days under sun and rain, brood on over the dumping ground.

Those familiar with T.S. Eliot's The Wasteland quickly catch the symbol and its deeper meaning, but those unfamiliar with Eliot's poem probably only regard the eyes as a component of Fitzgerald's masterful description of the barren landscape separating the skyscrapers of Manhattan from the lush gardens of Long Island. When I first encountered the eyes of T.J. Eckleburg, I was struck by the subtle obviousness of the symbol and the ethereal concreteness with which Fitzgerald employs it. Like all memorable symbols, Eckleburg's eyes to not impose themselves upon the reader in an overbearing manner. There is nothing domineering or tyrannical in its appearance. Nevertheless, it enters the text like a screaming whisper - muffled words transmitted in a language that is at once both foreign and familiar. Fitzgerald allows the ghostly quality of Eckleburg's eyes to linger and haunt the reader until the very end of the novel when the deeper implications of what the eyes represent is laid out plainly for those who lacked the eyes to see and the ears to hear what the oculist's billboard heralded near the beginning of the novel.

Wilson’s glazed eyes turned out to the ashheaps, where small grey clouds took on fantastic shape and scurried here and there in the faint dawn wind.

‘I spoke to her,’ he muttered, after a long silence. ‘I told her she might fool me but she couldn’t fool God. I took her to the window—’ With an effort he got up and walked to the rear window and leaned with his face pressed against it, ‘—and I said ‘God knows what you’ve been doing, everything you’ve been doing. You may fool me but you can’t fool God!’

Standing behind him Michaelis saw with a shock that he was looking at the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg which had just emerged pale and enormous from the dissolving night.

‘God sees everything,’ repeated Wilson.

‘That’s an advertisement,’ Michaelis assured him. Something made him turn away from the window and look back into the room. But Wilson stood there a long time, his face close to the window pane, nodding into the twilight.

The gently obscured symbol Fitzgerald gingerly erects in Chapter 2 shatters like a delicate porcelain vase dropped on the narrative's floor in Chapter 8. Many readers are repulsed by the heavy-handed nature of Fitzgerald's unveiling and liken Wilson's moralistic utterances to being struck by a falling piano, but I have always admired the simple sincerity Fitzgerald employs at this deep point in the novel. Like a magician revealing the secrets behind his tricks, Fitzgerald removes all possibilities for alternate interpretations of Eckleburg's eyes. A narrow variety of interpretations of the green light is permitted here, and there is space enough for these interpretations to curl up like cigarette smoke and linger for decades in the diaphanous air hovering over coffeehouse tables, but when its comes to the oculist billboard, Fitzgerald is both a spoiler and a tyrant.

The eyes of T.J. Eckleburg can mean one thing and one thing only. Needless to say, most readers find this non-negotiable quality of Eckleburg's eyes overly-simplistic and unsightly, but in my mind, it is precisely the quality that makes the symbol so memorable.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed